Ordinarily, photographing the Cuban military is prohibited, and just might land you and/or your camera in a Cuban military hoosegow. But Primero de Mayo (May 1) is Cuba’s version of Labor Day, and there’s a huge parade/march through Revolution Square in Havana with lots of military groups. Apparently, all bets were off on that no-photography rule during the parade.

Last week, I made my second trip to Cuba. A happy coincidence of timing put me right in the middle – literally — of the May Day parade. The whole thing is fully orchestrated, with (according to press reports) about 400 thousand marchers and with Castro’s government handing out the various flags and banners each group of workers will carry. It is a spectacle. The crowd paraded right through Revolution Square, past El Presidente Raul Castro, who succeeded his brother Fidel as leader of Cuba in 2008.

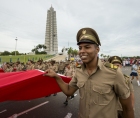

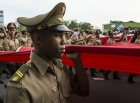

We arrived at dawn – jumping out of our cabs near the back of the parade staging area. I wandered right into the middle of the crowd of flag-bearing young people, then headed off to see if I could photograph the uniformed military personnel. Soon the throng started to move while I was in the middle taking some pictures, so I moved with it. I wasn’t completely sure if it was still “staging” or if the march had officially begun, because there were almost no spectators. Then I saw we were approaching Revolution Square, the site of the big Jose Marti Monument (Cuba’s ugly, creepy version of the Washington Monument). At that point it was clear that I was “in” the parade. Physically within, at least. I was in the fat middle of the military marchers as they chanted their way past the Monument, with President Castro looking on from the viewing stand.

Thousands of Cuban soldiers participated. Cuba has a mandatory military service requirement, so there are lots of 19ish-year-olds (male and female) in some form of “military” service. You do not get the feeling they are fierce warriors (though surely Cuba has some somewhere). I got no sense that they were unhappy about being “forced” to be there; nor did I get any sense of deep fervor or passionate ideological support of the regime. You just got the feeling they were a bunch of strangely-dressed teenagers looking to hook up on a Spring Break in Havana, chanting prescribed political slogans with about the level of intensity and sincerity a casual fan might show for his local college football team.

At one point I was walking backward, taking pictures of a group of 100 or so young soldiers walking along behind me. They got so preoccupied with following and “posing” for me (lots of flag-waving and thumbs-upping), they failed to hear (or to comply with) their commander’s instruction ordering them to stop. Happily, he was a good sport — especially when I rushed over to take several shots of him, to make sure he was in on the fun.

Cuba’s economy is very dependent on Venezuela, with whom Cuba has a doctors-for-oil exchange program that supplies Venezuela with semi-indentured Cuban healthcare workers, and supplies Cuba with at least a faint economic heartbeat. Venezuela’s Hugo Chavez died recently and Cubans seem worried that their support from Venezuela may be in jeopardy. Thus a major theme of the parade was solidarity with Venezuela. Signs, large and small, pictured Chavez and labeled him “Our Best Friend” (that’s Communist for “BFF”), which seemed a little odd since he’s dead and all.

Last year when I went to Revolution Square, the military guards barely let me walk around and take pictures at all, so being “allowed” in the middle of the parade as it went past Castro was unexpected to say the least. I carried two very professional-looking cameras, so they all seemed to assume I was a press photographer (which is ironic, because I spoke to an actual press photographer, and he did not have the same degree of freedom to move through the parade). At one point, I was asked (in very good English) what newspaper I was with. I blurted out (truthfully but nonsensically), “Soy de Houston! Tejas!” — as if I could fluently speak neither English nor Spanish. I gave a goofy thumbs-up and headed off to get lost in the crowd again.

I’m one of the last people on earth you’d ever expect to find at – much less “in” — a Communist-organized march extolling the virtues of socialist labor. But put a camera in my hand and a documentary mission in my head, and I’ll go almost anywhere. This was one of the craziest experiences of my life – and that’s saying something.

Posts from my spring 2012 trip to Cuba started here and ended here.