One of a series of posts from the Chindwin River in Burma (Myanmar).

Those statues of a fat, laughing Chinese Buddha are no part of Theravada Buddhism in Burma.

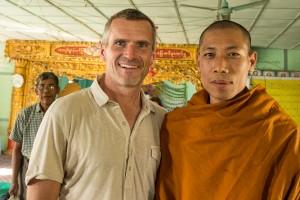

This tattooed monk lived at a hilltop monastery by the River in the Burmese (tribe) village of Ye Khar Tun.

Summarizing Buddhist beliefs and practices is like trying to summarize Christianity – recognizing that Christianity includes Mormons, Catholics, Amish, Presbyterians and Pentecostals. You can’t assume that any specific beliefs and practices are widely or universally shared. So the stories I got from our Yangon-based guide often differed from what we saw in the rural towns, and from what I learned as I tried to bone up on it.

Burmese people generally follow Theravada Buddhistm – as distinct from the various branches of Mahayana Buddhism that dominate in China, Korea, Tibet and Japan. Theravada Buddhists emphasize the older, original teachings of the original Buddha, Siddhartha Gotama, an actual human person who lived in India and died 2500 years ago. At least in theory, true Theravada Buddhists don’t think Buddha is (or was) a god; they don’t think he’s alive or that he (or anyone else) is immortal; they don’t think he (or anybody else) is up there answering prayers. They don’t believe in the Dalai Lama (that’s peculiar to Tibet, mostly); they don’t believe in that fat, laughing Buddha (that’s a more-recent Chinese invention). They believe in being good, doing good, and thinking good thoughts. Nirvana isn’t a heaven; it’s a state of mind without suffering.* In theory, they meditate over the philosophical teachings of the human they call Buddha, but in practice it sure looks like they’re praying to something that’s at least partly supernatural.

This lady is a yogi. It’s a little bit like a nun or monk, but as she explained it to us, yogis are more focused on helping people (especially the sick) and less involved in philosphical meditations.

Though the Theravadas reject deities and supernatural aspects of Buddhism, most Burmese people believe — to some extent — in an elaborate mix of “spirits” or “nats.” These nats can be like demons or trolls, like guardian angels, or like patron saints. The nat concept seems to be partly a separate animist religion, partly an element of Burmese Buddhism, and partly a very powerful set of superstitions. Most towns had some sort of shrines to a various nats – often right next to (or even on the grounds of) a Buddhist temple or pagoda.

This shrine — on the site of a Buddhist stupa — is actually devoted to one of the spirits (“nats”) the Burmese people believe in: that statue is NOT Buddha. The nats are sometimes akin to patron saints (of a town, for example); others are like little ‘gods’ of the seas or mountains.

Some of the nats are river spirits. Our boat (like most of the similar boats we saw on the river) had a couple of big bowls on top of the captain’s wheelhouse, each containing offerings (bananas, coconuts, flowers and water) to the river spirits, and a handful of flowers right on the bow. Despite the prevalence of domesticated pigs in the region, we never ate pork on the boat – because apparently the river spirits don’t allow it. The river spirits kept us from sinking, I guess. But they failed to keep us from getting stuck three times on sandbars.

Whatever the specifics of the beliefs, Buddhist buildings, statues, monks, and customs are an enormous part of life in most Burmese towns. It seems there are stupas everywhere. When we arrived in a town, we would almost always be quickly shown (with pride) the local monks or monastery. Multiple villages we visited encouraged us to stay for ceremonies at their temples. We ran across events going on at the monasteries. Even though the monks were always quiet and understated, they were clearly respected leaders in the communities.

In the grid above: The huge group of kids that seem to be dancing is in a pagoda building on a weekend (non-school day). We were told they were learning citizenship and patriotism and manners. I swear they stood there chanting and gesturing to the same song for at least 30 minutes, and we were told they were there for four hours every week. That group of five women had just left some sort of meditation class (led by a monk); they were apparently supposed to maintain their meditative state of mind (and keep their hands like that), so they were surprisingly tolerant of the group of photographers that swarmed them as they dispersed. That blue/yellow/red/white/pink thing is the flag of Theravada Buddhism. Finally, as I took that last image in the grid, our guide was explaining that local Buddhists had — despite their modest means — generously donated those standing fans to cool the place off. My joke, “Wow, they must be big ‘fans’ of Buddha!” got zero laughs and just one pair of eyes rolling.

* For God’s sake (pun-ish literality intended), don’t listen to me on matters of religion. These are just my impressions from a few weeks in a Buddhist culture and from a tiny bit of brushing up I did so I could better understand what I saw.