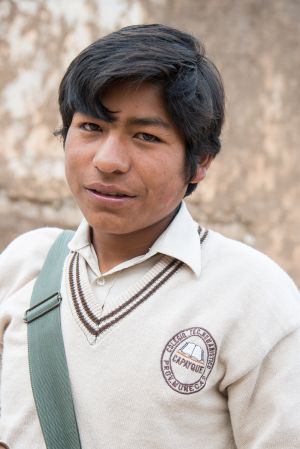

I sometimes make a hobby out of choosing a random side road somewhere in the world and just seeing what I find. —— I should make clear that these images are from Chissi, a town far away and very different from Capayque, the village that has been the subject of several recent posts.

I turned down the dirt road toward the Bolivian pueblo of Chissi just hoping to find a better view of the Lake Titicaca shoreline near the Strait of Tiquina. But as I drove down the hill into town, I could see some sort of event going on in a big field — with dozens of people all in bright pink costumes. Of course I drove right toward it.

As the pictures show, the men’s costumes were the gaudiest rhinestone-cowboy looking things you’ve ever seen – even putting aside the fact that they were hot pink. The women’s costumes were slightly less outrageous – Bolivian women wear those tall “bowler” hats and those broad skirts all the time as everyday wear, so the costume just spruced up their usual wardrobe profile and turned it pink.

It was the day after Easter, and apparently Sunday’s religious celebrations give way to a carnival-like Easter Monday celebration with lots of costumes, dancing, a town feast, and quite a lot of beer. I parked at the edge of the field and walked toward the action.

Besides my being out of costume, I was the tallest person in town, the only one with light-colored eyes, the only one with clipper-cut hair, and the only one who spoke English.* It took about 10 seconds before I was invited into their circle, about 20 seconds before I was presented with a cup of beer and about 2 minutes for the crowd to form around me for a group photo, then about another 2 minutes ‘til I was put into one of those pink vests and hats and instructed to pose for more ridiculous pictures.

The band (trumpets, baritones, drums and a cymbal) would play for 20 minutes or so (and the costumed folk would dance), then rest for 20 minutes or so (and the costumed folks would drink more beer). At about 1 o’clock, the whole group danced down a path through town; several of my new friends grabbed me and pantomimed “comidas” (food). We all ate the same thing: A bowl (no silverware) with a chunk of “carne” (maybe beef, maybe not), a couple of different potato-like things, a roasted-in-the-peel plantain, and some lettuce and tomatoes. It was a lot of food, but they’d made a big deal out of presenting it to the conspicuous gringo so I stuffed myself as best I could.

The photographic challenges were many. The Bolivians seemed to be either painfully bashful about being photographed or uncontrollable hams, with no real middle ground. I was almost constantly being tugged at and urged to take a different picture or try to answer a question. As is often the case, it was hard to both participate in the event and photograph it.

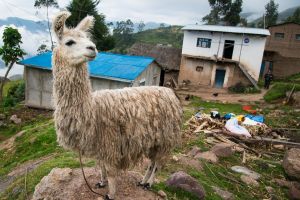

I showed these pictures to another Bolivian man from the opposite end of the country. He thought these were Peruvian traditions and costumes – and indeed Chissi is just 20 miles or so from the Peru border. For those readers who have seen my recent posts from Capayque (in the mountains on the opposite side of Lake Titicaca), I should emphasize that this is a very different area. Chissi is just a couple of miles from the main highway and — as the cervezas and elaborate costumes reflect — these folks clearly had a lot more disposable income than the people of remote Capayque.

I stayed about four hours in Chissi – scrapping my plans to visit the ruins at Tiwanaku that day and putting my pitiful Spanish to the test with the simplest communications. What country am I from? Yes, I think your pueblo is bien (or was it bueno?). Smile for a foto? Comidas? (Si!) Mas cerveza? (No, gracias, I’m driving back to La Paz this evening.) I wound up racing back to La Paz mostly in the dark, through a two-hour Bolivian traffic jam coming back into town.

There was a simultaneous celebration going on a few dozen yards away, which seemed to be some kind of harvest festival.

All this happened on my first full day in Bolivia – driving around by myself before I met the group in La Paz that went to Capayque. My habit of turning down random side roads in search of something interesting was surely rewarded once again.

I’d like to think that if a Spanish-speaking Bolivian stranger wandered into the middle of a small town festival somewhere in America, he’d be welcomed and embraced to a similar extent, but I don’t know if that’s true. Let’s hope so.

– – –

* I suspect I was also about the only adult who was wholly sober, and the only person with any substantial amount of hair on his face or arms. It seemed like I may also have been in a minority who had no visible gold on the their teeth.