This is the last of my posts from a May 2013 trip to Cuba. The first was here. The ten posts (with tons more pictures) from my 2012 trip started here, and ended here. Most of what you see below are just typical sights on the streets of Havana. They are not odd, atypical spots. The rooftop shots are Parc Central, but regular street scenes you see are what virtually all the streets look like.

After my 2012 trip to Cuba, I had separate posts highlighting the classic cars that roam the streets, the glamorous Tropicana, Cuban “patriotism” and education, a rooftop ritual, Cuban athletics and just everyday life in Havana. Returning to Havana just a year later, I necessarily saw many of the same sights, as the pictures above reflect.

The most important “new” feature of the trip this time was the opportunity to see some of it through the eyes of a Cuban-American woman– “Didi” — whose family was very involved in the turmoil of the Revolutionary period, and who was visiting Cuba for the first time.

Didi’s parents left Cuba in the early 1970s – escaping first to Spain and then to the United States. She had an uncle who was a political prisoner of Castro for more than a decade – apparently because he worked for a telephone company. Her father faced a regime firing squad but was somehow spared at the last minute and sent back to work. A close family member escaped to Florida on a raft. An aunt was evacuated by the American CIA and the Catholic Church in the “Peter Pan” project – where parents gave up their children and sent them to the U.S. because they believed (rightly or wrongly) the kids would otherwise be forcibly interned by the Cuban Revolutionary government. The family friend who was to have been the organist at her parents’ wedding was shot – apparently by government forces — on the church steps a day before the ceremony.

Americans who think all Revolutions are hip and who flippantly don “Che” Guevara T-shirts ought to spend a few minutes with a family like that.

Didi had never been to Cuba, and was on a personal mission to visit her family’s old apartment, her parents’ church, and her father’s school. Mostly she wanted to see the country that her parents lived in and left – the world that she’d have grown up in had her family not been brave and determined enough to find a way out. We saw in Havana the three-room concrete-floor apartment where she would likely have grown up. We saw the kids in the street and the people on the balconies — living the life she most likely would have had to live. She cried a lot; I tried not to cry along. I know it was a profound experience for her, because it was deeply moving even for an Oklahoma boy who had no stake or connection to Cuba (except for his new friend Didi).

Didi is now a 30-something pediatric ICU physician, married to a pediatric oncologist. Her brother is a successful lawyer in a Washington DC firm. If she’d lived in Cuba, she would have grown up going to a school where she had to stand up every day and pledge allegiance to the Communist regime. And she’d probably be making about $25 a month, working in whichever government job the regime instructed her to work.

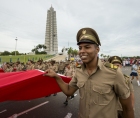

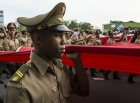

The first shot just above is Didi’s family’s apartment; my ultra-wide-angle lens makes it look bigger than it really was. The second shot is during the May Day parade (about which I did a prior post). I was not yet aware of her family’s history when I yelled “come with me” and led her into the midst of a few thousand Cuban military — I can only imagine how crazy that must have felt. The dark shot at the Tropicana has Didi on the right, with our mutual friend Patricia, who — like me — was privileged to share some of Didi’s quest, on the left. The other shots are just a couple of strangers she met and embraced (literally) along the way.

============

A year ago, I wrote a post about the American embargo against Cuba. The embargo (“El Bloqueo”) continues to be an enormous focus of attention. My thoughts a year later are, hopefully, clearer and deeper, but ultimately the same: You can legitimately debate the embargo’s ongoing rationale and effectiveness, but its roots and goals are noble. More critically, it is not to blame for Cuba’s pitiful situation. It is not America’s fault that a chaotically organized socialist economy that is based on governmental control and oppression operates very poorly and impoverishes its people. Policy change is definitely needed – but it will have to start in Havana.