Here’s the first of a handful of posts from a recent visit to Istanbul, Turkey.

Napoleon once said that if the world had just one capital, it would be Constantinople – the city now known as Istanbul, Turkey. Apparently lots of Emperors and Sultans felt the same way. For over 1000 years, Istanbul was Constantinople – capital of the Eastern Roman Empire and named for the 4th Century Roman Emperor Constantine. In 1453, the Ottoman armies of Sultan Mehmet II successfully laid siege to Constantinople and established Istanbul as the new capital of the Ottoman Empire.

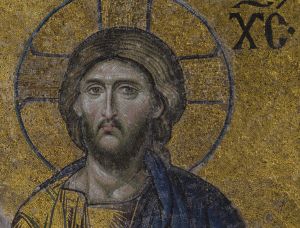

The Sultan and the Ottomans were Islamic, so most of what is now Istanbul has been mostly Islamic ever since. Grand Christian churches were converted to mosques. The grandest of all was Hagia Sophia — originally dedicated in the year 361 and serving as a Christian church for nearly 1100 years. When the Ottomans took over in 1453, the crosses and other Christian symbols that covered Hagia Sophia’s walls and ceiling were replaced with symbols of Muhammed and Allah. A mihrab and minbar replaced altar and pulpit, and minarets (towers used for the daily call to prayer) were built on all four corners. Fortunately, the enlightened Sultan only covered up – and did not destroy – many of the Christian religious icons. Today the Hagia Sophia is a museum, showing off its immense and beautiful architechture and its odd current mix of Christian icons and Islamic symbols, and thus telling the story of Istanbul’s last 1700 years.

The tiny Church at the Chora monastery a few miles to the west saw a similar fate. Today it’s a museum, and most of the amazing and elaborate murals have been restored.

*”Istanbul (Not Constantinople)” is a goofy song about the re-naming of Constantinople. It was a gold-record hit in the 1950s by the Four Lads, and was recorded again by the They Might Be Giants in the 1990s. If you don’t remember it, watch the recent version on YouTube. It’ll make you smile. “All the girls from Constantinople are in Istanbul (not Constantinople); so if you’ve a date in Constantinople, she’ll be waiting in Istanbul.”