Number 4 in a series that started here.

I don’t smoke. Not even cigars, and not even cigars when I’m in Cuba. But of course the Cuban Cohiba is the Holy Grail for cigar lovers, and cigars are among the iconic symbols of Cuba. Apparently the Cohibas go through a unique (and secret) fermentation process that creates a distinctive taste. Legend has it that Fidel Castro himself “discovered” the Cohiba blend. Another legend (though apparently true) is that poisoned or exploding Cohibas were among the dozens of ways the American CIA devised to attempt to assassinate him. Given all this history and mystique, I was glad we got a chance to see some of Cuba’s rural tobacco country.

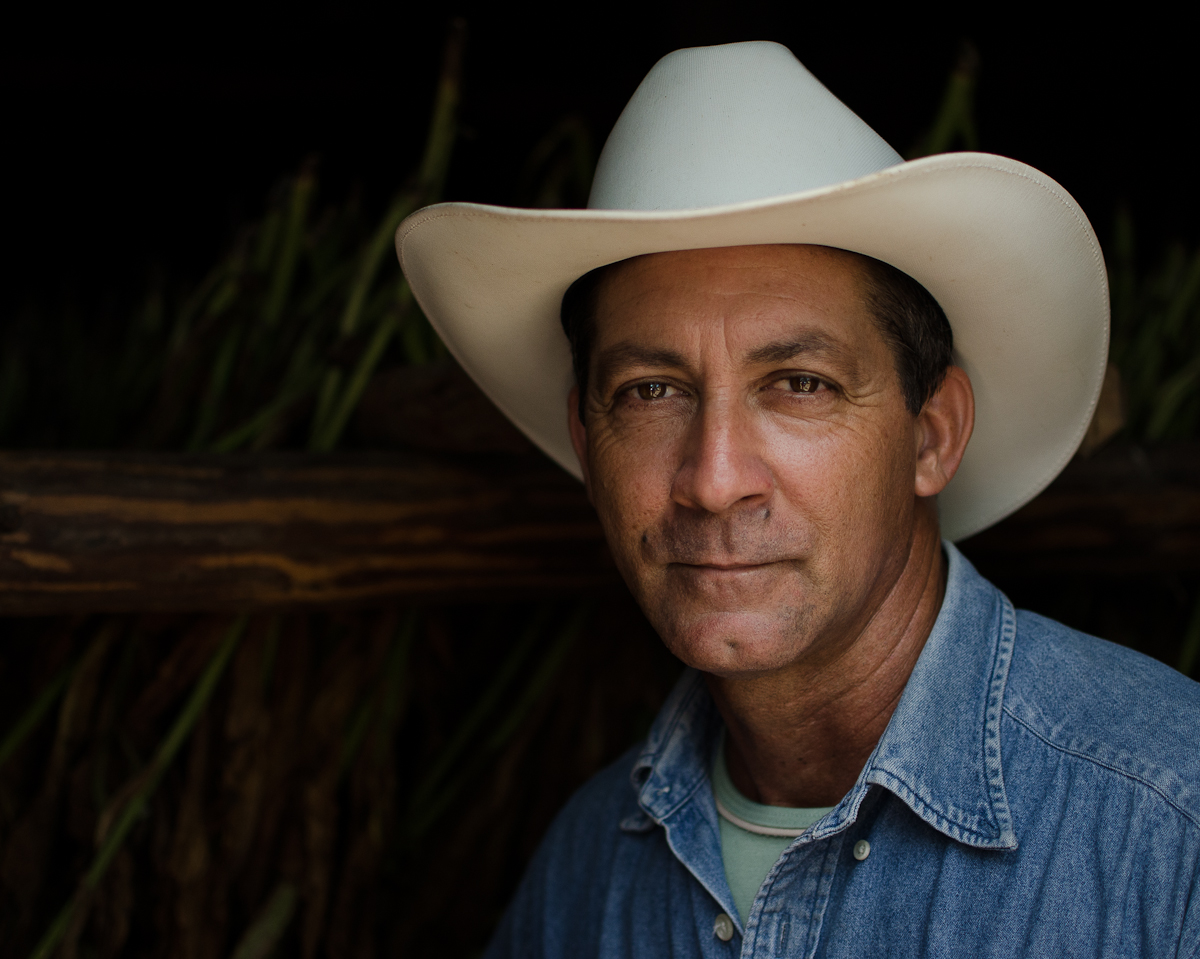

These pictures are from the Pinar del Rio province in far western Cuba, in the countryside near Vinales, a couple of hours west of Havana. The guy in the clean, slick cowboy hat is Marcelo Montesina – described in at least one write-up as the “King of Cohiba.” He runs one of the few, elite tobacco farms that provide the tobacco leaves used for the real Cohibas. You won’t have trouble distinguishing him from the less-elegant-looking farmhand pictured standing in a tobacco field outside a thatch-roofed drying house (holding the dried-up tobacco leaf was his idea). The guy sitting at a table is rolling the leaves into a cigar (mostly for our amusement – real Cohibas are rolled only in government-owned factories in Havana). The mustached man smoking a cigar is a garlic peddler at a little market in Vinales. (Continued…)

We ran across a little festival in the town of Vinales. It looked about like what you’d see in most any Latin American country (or maybe most anywhere) — simple carnival rides, lots of street food for sale, temporary tattoos (Che Guevara tattoos seemed especially popular), sunglasses, T-shirts. Nice to see that communism/socialism hadn’t crushed simple traditions like this. They sold beer out of tank trucks — imagine a 200-gallon water tank as a “keg.” You needed to bring your own bottle to be filled out of the tank, and there were guys standing around eager to sell you an empty used plastic water or cola bottle if you’d failed to bring your own.

The pink building is a hotel we passed on the way home. The inside looked pretty spartan, but the outside made a nice picture just as the sun set.