I promised myself I wouldn’t let a full year go by before finally sorting through (and sharing) my photos from a 2018 trip to Morocco.

If you’re reading this, you probably know that I love to travel to new, unusual places. And you probably know that I enjoy almost all those trips and generally come home telling mostly-positive stories even about places that have plenty of oddities and problems. (See, for example, my reports from Cuba and Iran and Myanmar and Colombia and Guatemala . . . .). I’m pretty open-minded (or at least non-judmental) about cultures very different from my own. But there was something ‘off’ about Morocco. Although the small group of folks I traveled with were unbeatable, and though the trip was expertly planned and the accommodations as swank as I could ever have hoped, I wouldn’t count Morocco among my favorite destinations.

I expected (naively, I suppose) Morocco might be similar to Iran — where I’d had a truly great trip in 2017. It wasn’t. I think the counterintuitive problem is that, unlike Iran, Morocco has long been an established and popular tourist destination for Americans and Europeans. (Bob Hope and Bing Crosby sang “Off on the road to Morocco” and Humphrey Bogart did his play-it-again-Sam in Casablanca in 1942, though both were actually filmed in the American Southwest.). In Iran, people were just excited to see and meet American visitors intrepid enough to trapse their cities and deserts. In Morocco, they learned long ago that “visitors” are “tourists,” and tourists are revenue sources.

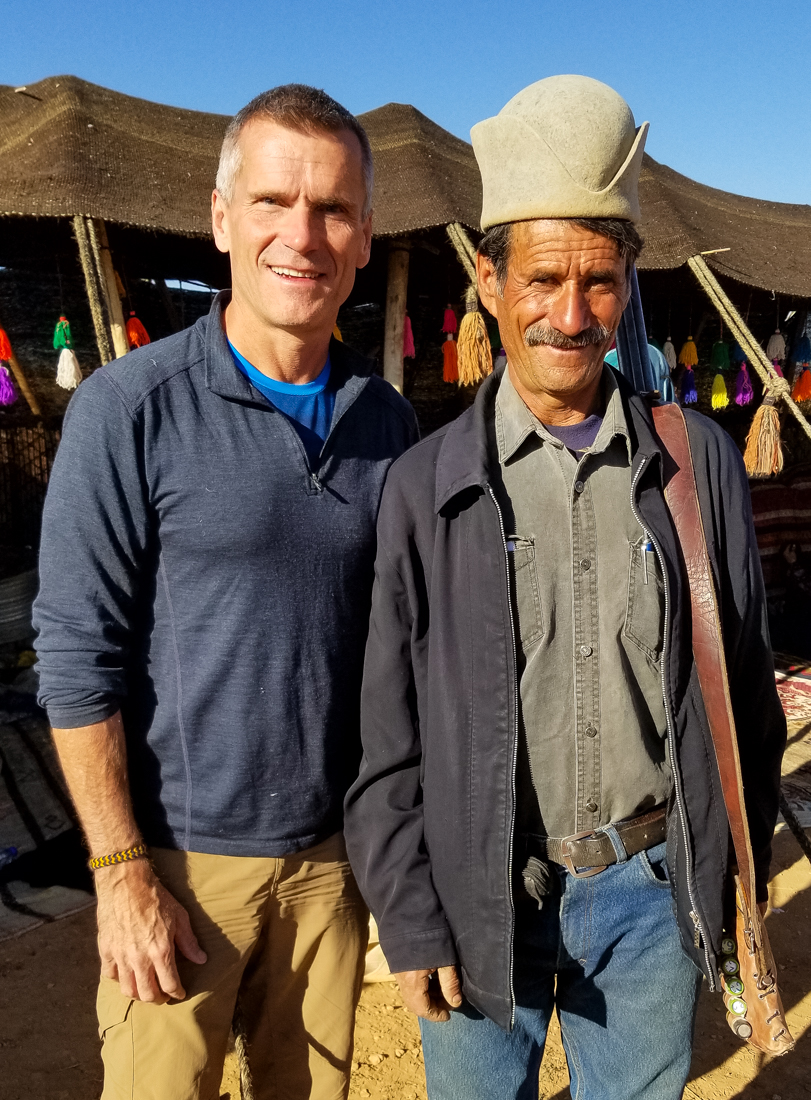

My pictures from photography trips usually include lots of images of local people. But you won’t see many people here. Almost everyone I photographed (or tried to photograph) asked for money in one way or another. That’s something I try to avoid: to me, it can ruin the authenticity of both the experience and the photograph. Others just shooed me away entirely — which I actually prefer. Some would actively invite you to take their picture — only to expect payment when you did. It was hard to know what you were getting into.

It’s fine when people don’t want to be photographed — I completely respect that. And there’s nothing inherently wrong with them doing it only if they get paid. I’m just not usually interested.

I was fascinated at how quickly so many locals morphed from entrepreneur to beggar to extortionist. Their initial approach was to try sell you something you clearly did not want (kids trying to hand you an obviously worthless trinket or adults giving unrequested, intrusive ‘guide’ services). When that failed to generate a cash response, they’d often keep their hand out and just ask for money. When that failed, they often did not give up: uncomfortable persistent harassment was not uncommon.

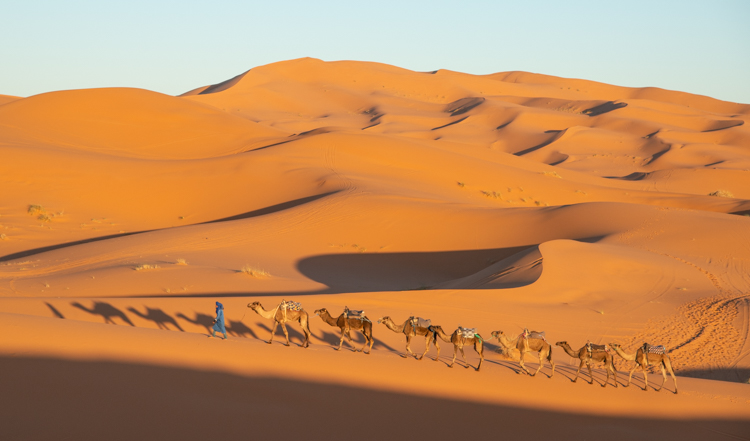

My whole complaint about visiting Morocco is the lack of a feeling of authenticity. The country’s biggest mosque — The Al Hassan II in Casablanca — was built in 1993. Up close, it looked more like a Las Vegas mock-up than a real or historic or sacred site. Morocco sits at the edge of the Sahara Desert, so twice we paid local guides to get us deep into the desert, but both times wound up on well-trodden sand within sight of highways and hotels. And those pictures below of the camels in the desert? Of course they’re a set-up. A guide dons the traditional robe as part of the gig, and knows just where to lead the herd at sunset for the best photo opportunities. Fun to do and see, but not as real, authentic cultural experience. It’s just hard to be anything but a touristy tourist in Morocco.

The “snake charmers” I saw all over Marrakech’s market square on my first evening in the country proved to be something of an omen for the rest of the trip. The snakes are de-fanged, so it’s all rather faked anyway. They’re not “charming” for the sake charming; they’re there as a tourist draw. If anyone comes even close to raising a camera in their direction, a couple of those “charmers” would aggressively rush over with their hands out, preventing any photos until and unless you ‘tip’ them. And the nasal-sounding ‘flute’ playing is terrible. I just skipped it and went looking for a diet coke.

+ + + + +

Another odd feature: Flags. As we drove through the countryside, there were Moroccan flags everywhere. Tiny villages would have 100s of flags installed along the roadside. Flags were sometimes every 100 yards or so on completely unpopulated stretches of highway. Imagine the most flag-obsessed town in America on the Fourth of July: this was pretty much every town, every day. But these were government-installed displays and they felt very different. Maybe it was the ugly all-red flags (with a green ‘pentagram’ star), or maybe it was knowing that Morocco is governed by a sometimes heavy-handed king, but this had no feel of authentic patriotism. It felt more like a monarchical government reminding you that it was everywhere.