Riding a float in one of the big New Orleans Mardis Gras parades isn’t like you probably think. Everybody seems to ask me the same question: I’m sure I threw at least 2,000 strings of beads, cups, toys, or footballs (roughly one every five seconds for over three hours), and never saw a bared female breast. That happens over on Bourbon Street – but not much on the parade route.

I did see lots of kids having great fun, usually with their friends, parents, grandmas or grandpas close behind. People on ladders so they could see above the crowd. Lots of college kids acting silly. Groups on balconies in sportcoats and party dresses. Lots of pretty young girls, and lots of not-especially-young-or-pretty girls. Grown men and women jumping up and down, genuinely delighted to get even a fifty-cent trinket thrown at them from a masked man on a tacky float. I’m sure a large percent had had a bit too much to drink, but happily it was hard to tell from my perch up on the top deck of Float #20.

One of my float neighbors, Houstonian Tommy Miles, ready for the Bacchus parade with beads organized atop our float

You don’t just sling beads at the blur of the crowd. The vast majority of those 2,000 strings of beads I threw were aimed at a specific person with whom I’d made eye contact before making a targeted toss. They break eye contact to catch the beads, then usually look back up with appreciation so we could jointly celebrate our successful connection with a mutual fist pump. You’d have also been impressed with my bead-flinging accuracy – even underhanded, leaning over the rail atop a moving float, throwing gangly strings of varying weights, a majority went to the intended receiver.

Here’s a side note to you 20ish-year-old males out there: If you stand near a little kid, a grandma or a pretty girl and jump to intercept beads being thrown to them, you’re an idiot (and something that starts like “dude” but rhymes with “swoosh-tag”) – and the gods of Mardis Gras karma will ensure that none of those pretty girls out there will ever even speak to you.

Another of the riders on my float – a guy from somewhere in central Louisiana who (initially) stood right next to me — had a different experience. I didn’t learn much about him – he passed out about a quarter of the way into the parade. This is not especially uncommon, so we just left him on the floor. I didn’t drink anything but Diet Coke and a bottle of water (and fueled myself with a couple of mid-route Powerbars), and I’m very sure I had a lot more fun than he did. Maybe I should have explained to him the hilariously ignored New Orleans Ordinance prohibiting drinking on the floats?

Most of the pictures here are from my day riding a float in the Bacchus parade. You spend an hour or two organizing your “throws” (mostly bags of beads), then get your costume mid-day. The masks are mandatory; you can literally be fined for not wearing one. You also have to wear a harness underneath to clip yourself onto the float (for reasons perhaps made obvious by the prior paragraph). Our float was assigned alligator costumes. It takes a pretty strong sense of tradition to get a big group of straight Southern men into matching costumes with sequin sleeves and a crazy pink collar.

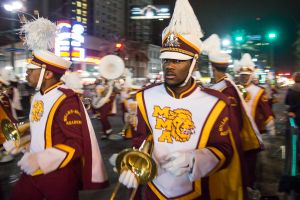

The floats roll mid-afternoon to the staging area — a neighborhood right next to the Mississippi River with several tiny local bars that probably don’t see a lot of middle-class white guys any other week of the year. Imagine 1500 or so grown rednecks dressed in those satiny, sequin pajama-like costumes converging on an urban neighborhood. It takes another three hours or so to navigate the parade route through the Garden District , downtown along the edge of the French Quarter, and through the middle of the already-booming party in the Convention Center. We arrived at the party after 11pm. It’s a formal “gala”-type event where ladies must wear floor length gowns, but only half the men are in tuxedos and the other half are in those goofy costumes. Styx played at midnight, and everybody headed to the casino around 3:30 a.m. I saw more than one New Orleans sunrise on this trip, and I surely never got up early.

In 2012, I told the stories of how the Mardis Gras “krewes” put on the parades here, of how – even amidst the chaos – New Orleans can be as civilized as you choose it to be, and how you calculate the day and time of these Mardis Gras parades. This year I had higher hopes for my Mardis Gras photography, but much of that proved incompatible with the preference to spend most of my time hanging out with the couple of dozen friends that were in town for the festivities. These won’t win any prizes, but hopefully they’ll at least give a good feel for what it’s like to see and to ride in a big Mardis Gras parade. Laissez les Bons Temps Rouler*

*Of course “Mardis Gras” is a French term (“Fat Tuesday”) and its events are centered in the French Quarter; “Laissez les Bon Temps Rouler” is a popular Mardis Gras slogan, French for “Let the Good Times Roll.” “Bon Temps”: good times.