Most of my September trip to India was in the Ladakh region of Jammu & Kashmir, in far north India near the Pakistan border. Everything there — the people, the terrain, and the religion — looks more like Tibet than India.

Golden prayer wheels and images of a musical Buddha at the temple entrance at Themisgan Buddhist monastery in the Ladakh region of India.

Hinduism was a primary defining feature of modern India as it was partitioned from Muslim Pakistan in 1947. The names “India” and “Hindu” both come from the same Sanskrit word for the Indus River, which runs through the Ladakh region of far northern India. Somewhat ironically, though, Ladakh is unique in India: most everyone is Buddhist – except for a few Muslims near the Pakistani border.

A young monk serves tea as part of the early morning prayer service at Thiksey monastery in Leh, Ladakh, India.

The Buddhism practiced here bears little resemblance to the Buddhism I saw last year in Myanmar (Burma). As I described last year, Myanmar’s Theravada Buddhism is a simple philosophy and barely a religion at all. They learn to think good, peaceful thoughts and try to do good things. To the Theravadas, neither Buddha nor anyone else is divine, immortal, or supernatural. They don’t really pray; they meditate. The Burmese monks are humble and quiet, and their monasteries are modest community meeting halls. But everything Buddhist looks very different in Ladakh.

The statues with 12-armed, horned, and 3-headed Buddhist “protector god” icons are kept covered in drapes.

India’s Buddhism is mostly a form of Mahayana Buddhism – sometimes called Tantric, Tibetan, or Vajrayana. The rituals are elaborate (think chants, horns, drums, and bells). The monasteries are often castle-like (indeed, some are actual former castles), their temples decked with colorful and elaborate tapestries and paintings. Worshipers prostrate themselves as they arrive. There’s a hierarchical pecking order among the cloistered monks and lamas (up to and sometimes including the powerful Dalai Llama). Prayer wheels and prayer flags are everywhere. There are idol-like statues or paintings on the temple walls of various “tantric deities” or “protector gods” – some with multiple heads, a dozen arms, horns, swords and blue skin, wearing voodoo-like human-skull-decorated hats. And that’s not even the strangest part (let’s just say there’s a good deal of unsubtle sexual symbolism). They believe in reincarnation generally, and believe that their high priests are literal reincarnations of their ancient priests. We even heard their version of an end-of-the-world apocalypse.

To most Americans and westerners, the complicated tales of how they scour the region’s villages to locate a 3-yr-old reincarnation of the supreme religious leader are hard to fathom — much less accept and believe — as are the seemingly convoluted explanations of those statues, symbols and rituals. But of course, all the themes of Christianity and Judaism that are familiar to us surely sound bizarre and ridiculous to them. As is so often true in international travel, learning about other cultures can teach you as much about your own culture as it does about the foreign one.

This voodoo-looking Buddhist gargoyle is on the roof of Deskit monastery, overlooking the Nubra River valley in northeast India, just a few miles from Pakistan.

Buddhism expert Dr. Khenpo Konchok “Lama Ji” Rigzen, through some of the Buddha tapestries at Thiksey Monastery in Leh, India.

A Buddhist chorten (monument) and prayer flags, underneath one of the 20,000+ peaks in the Suru valley. This marked our return to Buddhist territory after a day or two in the muslim region near Kargil.

Late evening sun on Thiksey monastery, seen from the “Shey Palace” monastery, a former ruler’s castle near Leh, India.

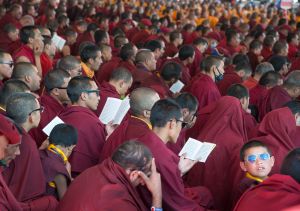

Monks return from their visit to the “throne” (upper right) of His Holiness the Gyalwang Drukpa during the 1000-year Naropa Festival in Hemis, India.

NAROPA 1000: Once every 12 years, the Drukpa Order (a sect or denomination of Buddhism) celebrates its Naropa Festival in Hemis, just south of the small city of Leh in Ladakh. By coincidence, I was there during part of the festival. I missed the highlight — when His Holiness Gyalwang Drupka (this sect’s equivalent of the Dalai Lama) dons the 1000-year-old crown and jewelry of the sect’s founder, but did get to watch His Holiness receive gifts from pilgrims and deliver a long, monotone sermon. That’s him sitting on the golden throne, atop that pyramid temple. No kidding. Somehow I stumbled into a front row position for a few minutes (with thousands of monks and worshippers up the hill behind me). It was definitely one of those moments when I pause, laugh, shake my head, and marvel at the wacky situations I’ve been getting myself in the middle of.

The U.S.-built canal has six pairs of locks – three up and three down — that raise boats to an elevation of 85 feet for most of the passage then lower them to the opposite ocean. The physics are driven by the good fortune of a major river (fed by seasonal tropical rainfall) in the middle of the isthmus. It’s dammed to make a huge lake, and water flows out in both directions – into both the Pacific and Atlantic – filling the locks along the way. The locks are in pairs to allow two-way traffic.

The U.S.-built canal has six pairs of locks – three up and three down — that raise boats to an elevation of 85 feet for most of the passage then lower them to the opposite ocean. The physics are driven by the good fortune of a major river (fed by seasonal tropical rainfall) in the middle of the isthmus. It’s dammed to make a huge lake, and water flows out in both directions – into both the Pacific and Atlantic – filling the locks along the way. The locks are in pairs to allow two-way traffic.